Eyzel Torres, Writing Center Tutor Alumni Profile

1/27/23 Interview with UIC Writing Center Tutor ’22 alumna, Eyzel Torres

1/27/23 Interview with UIC Writing Center Tutor ‘22 alumna, Eyzel Torres

- Pronouns: She/her/hers

- Graduated: Spring 2022 with major in Rehabilitation Sciences, minor Disability and Human Development and minor in Life Sciences Visualization

- Took 222: with Kim S18

- Tutored: S18 until graduation in S22; currently works as Writing Center supervisor

- Currently: earning Master of Science in Biomedical Visualization, expected graduation S24

How would you explain your current Master’s program in Biomedical Visualization to someone unfamiliar with it?

So I think the simplest way to explain it would be the study of medicine and pairing that with art. So how do you teach medicine using illustrations or animations, 3D models, graphic design. So it’s just the science of medicine using art to help others understand it.

And what kind of classes do you take for that? How big is the program as well?

Actually, our program here at UIC has the biggest number of students. There’s four programs in North America. There’s one in Toronto, and one at John Hopkins. . .Our program, my year, like my class, there’s, I think, 22 of us, but most others have, tops, six students per graduating year. So ours is really big compared to others.

Does it provide any funding or GA ships to help with tuition?

Yeah, there’s a couple of different options for financial help. Actually, most of my classmates are in TAships right now. So they’re just TAinh for undergrad and that comes with a tuition waiver. And then the actual college, the program itself, also offers different—I guess they call them like fellowships? So like, they actually just came up with one to help another student for a whole year where they would be creating content for like their website and just keeping the website for our Master’s program. And there’s another position where we basically take care of the lab because we have a computer lab where we have all of our programs like Photoshop and 3D Max and Maya and just all the programs that we use in our classes. So we have a position where someone is basically taking care of the lab and making sure if there’s a problem with computers, IT knows and to keep everything just, like, tidy, and that position also actually takes care of our our skeletons, because each student has a box with a human skeleton which we can use to study anatomy.

Like your own private skeletons?

Yeah. And apparently, in past classes, they used to be able to take those boxes home, but we can’t do that anymore because there was like some sort of law or something where like you can’t really be transporting them. I’m not sure what it actually is. But I think it’s out of respect to for the donors too. Because we still have access to them here like in our building, but we just can’t take them out.

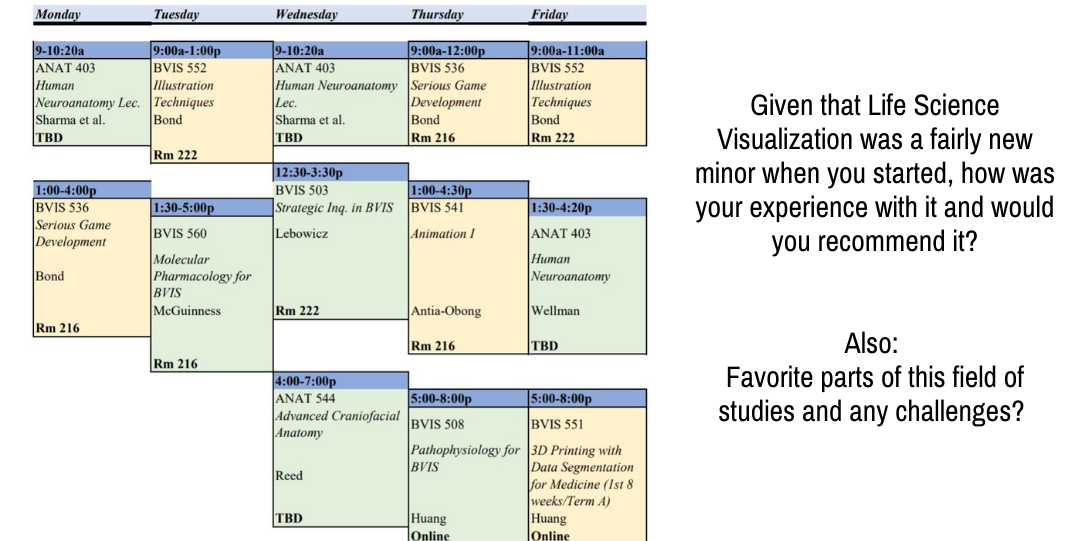

And then for actual classes that we take, we take anatomy, neuroanatomy, cranial facial anatomy, molecular pharmacology, physiology—so like those types of classes that are the hard sciences. And then we also take Introduction to Illustration Techniques, where we deal with like, oh, How do you use line? how do you use weight? Just like a traditional art class. And we have Animation, where we mostly focus on 3D animation, and how to create molecular animations, which is like not my cup of tea, but it’s fine. And we have a class on 3D printing. So I’m not taking that, but I’m hoping to take it next semester, because it sounds really cool.

Yeah, that’s really cool. So you mentioned that you’re studying these hard sciences, and then you’re studying art. Are these teachers from the art school and from the science school or is there a faculty specific to this program that knows each other and works in concert?

Yeah, so actually all of the faculty in our program, like the core instructors, all graduated from the program. So they all went through all of this and then came back. Our director, she actually was offered a position as a faculty, like right after she graduated. And then she came back later and became the director, which is cool. Then some other faculty, they worked out in the field for a couple years and then they were just. like, adjunct professors, and then some ended up staying full time.

Is it the case that most of the faculty are both knowledgeable in the hard sciences and are artists, so they have both skill sets?

Yeah, everyone on the faculty is a medical illustrator.

What are the different paths that people take with this degree, the different settings in which people work? And what appeals to you?

That is a really good question, because there’s so many different things. . . Some of the the people who have graduated from this program went on to work for 3D animation, where they either create the storyboards or the scripts or the actual 3D objects or they make the animations—that whole track. Some went into creating images and illustrations for journals, because there’s a medical science journal, it’s called JAMA. And some actually went on to do that for a living. Others actually went on to do freelance. So like if someone has a project and they need scientific illustration, some of the alumni, actually, that’s all they do is like freelancing. Others work in interactive. So they’re creating VR (virtual reality) and AR (augmented reality) programs.

So kind of like Pokemon Go, how you have the actual, like, where you are and then little Pokemon comes up? So things like those, but for medicine. And from what I’ve seen a lot of folks that work in that type of work, they either create apps, or they create games to teach, for example, surgical procedures to someone who is going to be a surgeon, so before they actually practice on a human or even on a mannequin, they play the game or they do that and they go through the procedure in the augmented reality.

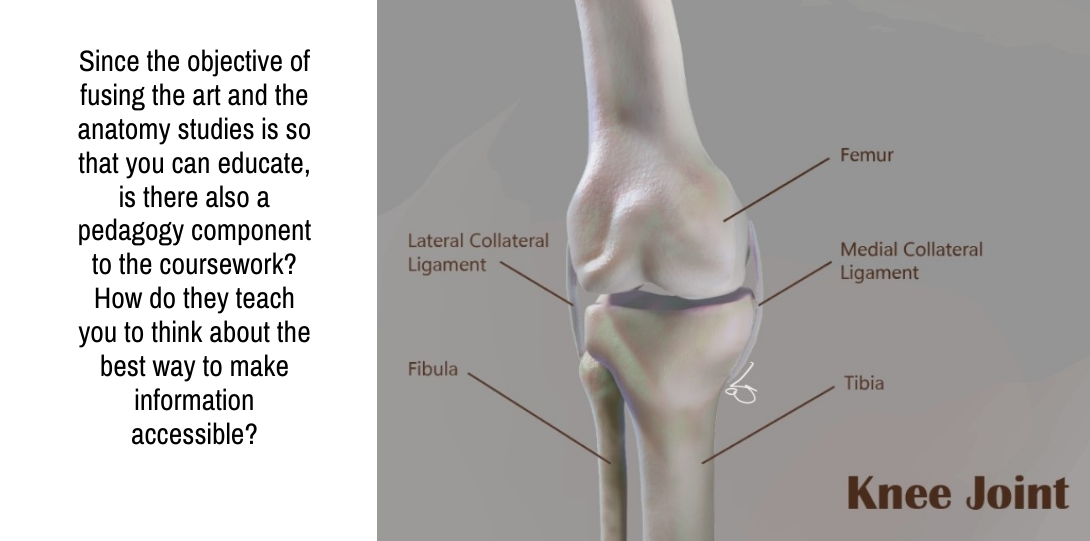

So since the objective of fusing art and anatomy studies is so that you can educate, is there also an education or pedagogy component to the coursework? How do they teach you to think about the best way to make information accessible?

Yeah, actually some of our classes do focus on it, and I forgot to mention them, but we take those types of classes—because we start in the summer—and those are our introductory courses as well, like, we read papers on different ways of teaching, and how we can implement them ourselves. And then we also look at teaching that is maybe not as effective and why it’s not effective and how we can use that in our career—that type of research.

So yeah, there is a lot of that also meshed into our other courses as well. So for example, in one of my illustration technique courses, we think about the composition, for example, and think about our audience. So that’s always the first thing we think about before we actually create something is who we’re making it for and why—so like, what are the goals and who actually is going to be looking at this? And so we have to think about either adjusting the language like, you know, should it be like eighth grade reading level for an adult who maybe is in this population versus if we’re going to be teaching doctors, you know, and they can handle jargon.

And so they always kind of intertwine those, like how to help people learn—like the education aspect—into the classes, whether it’s the art part or science. Because, like, for my pathophysiology class, we’re learning about different pathologies that can affect humans. But we also have a project where we’re supposed to look at the different imaging techniques. So for example, like, Oh, when can you use an ultrasound or when is an MRI or CAT scan better? And to think about how and why we can use the different things that are at our disposal, to help people understand what is going on with technology.

So given that there’s actually quite a range both of audiences and genres in which you might be publishing your work— everything from journals to posters for children to high tech augmented reality surgical apps for surgeons in training—what part of it is most interesting to you at this point? Or are there several things? And in terms of the work itself, what part of the design process is most fun for you?

So I have always wanted to go into public health education. And so for me, my background is that I come from an immigrant community. And not everyone in my surrounding community always spoke English. And so I was always a mediator when it came to going to clinics or going to the hospital and things like that. So I always grew up seeing a gap in understanding for not only my community, but others as well. And so I always knew that I wanted to go into something that would help mediate that in healthcare. I also knew I didn’t want to be a physician. Like I would I just would not be good at that. So when I was in high school, I took a cell biology class and my teacher at one point had just mentioned, like, Oh, yeah, there needs to be more medical illustrators in the world. And I was like, Medical illustrator, what the heck is that? And so I looked it up and I had talked to my teacher and I was just like, Oh, I’m interested to learn more about this. And so he explained what that field is to me. And I saw that UIC had a program in that, and since I grew up in this area, I was like, Oh, that’s so close to me, I could literally go there. And so I had basically decided, when I was like 17 or 18 or something, I was like, That’s what I’m gonna do, and I never had a plan B. And people would always tell me like, Oh, you need to have a plan B and I was just like, Nope, this is what I’m planning to do, that’s it.

And so, because I was also always interested in art, for a while, actually, I wanted to be a graphic artist, but people were always telling me that I shouldn’t do that because there’s like no money in it. And I would have to be really, really good to make it in the field. And I actually knew a family friend who went to school to be a graphic artist and like, they told me not to do it. They’re like,This would be the worst mistake of your life if you pursue this career. And it’s like—Oh, okay.

And so then when I realized that there was actually a little niche field where it is art and it is medicine, I was like, I can’t do anything else. Like, this is it for me.

And so I actually applied to the Master’s program at the same time that I applied to UIC as an undergraduate. Because, yeah, because they have this program that’s both a guaranteed professional admission or something.

Yeah, like GPPA? I didn’t know they did that for Biomedical Visualization!

Yeah, I didn’t either. And I had to submit my portfolio at the time. And I had to write some sort of essay about why I wanted to do that. And then I also have to apply to the Honors College to be a part of the GPPA. And so then I applied to the Honors College and I got in and I was like so excited, because I was like, Oh, this means that I do have a chance at getting into the GPPA program. And so they had told me that I was accepted just as long as I was able to complete my undergrad degree and take certain classes. So some other required classes were anatomy with a lab and I had to take at least three science classes, and I had focused on neuroscience, just because that was something that I was interested in and at least two different media for art. And so since I had the minor in life science visualization anyway, I had already checked off all those boxes anyway.

And so I, during the entire undergrad career, I knew that I was going to be in this program. And so I tried to see what I liked about the field and where I would want to go to. And so because I was taking all the disability and human development classes, it kind of emphasized even more in my head of like, Yeah, this is what I want to do because I want to help people that are not necessarily always being able to access like medicine, which is like really important to me. Because I feel like having a healthy —it’s not just your body, it’s like a healthy body and mind and soul and everything. And I’m interested in holistic medicine too, which I don’t know if I mentioned that. But taking those classes, it made me realize how many people really don’t have access. And just thinking about the social justice aspect of things. Like the U.S. has good advancements in technology and medicine, but that doesn’t mean that people can access it.

And so for me, going into this field—I know a lot of people are interested in helping doctors and physicians and surgeons and all of those learning medicine to be able to practice. But for me, it’s moreso of like I want the general public to know about their own bodies, what their own minds are capable of. Like, how to not necessarily wait until something bad happens where they have to go to the hospital or they have to go to a clinic. It’s moreso of preventive medicine, where if you know what, for example, a heart attack feels like if you’re a woman, because that is different than from when you’re a man or at least, biologically, like male and female.

So if you know when to catch signs, or you know what different pathologies look like or what they feel like, it’s easier to at least try to get treatment earlier versus not knowing anything at all until one day it’s just so bad that you have to go get health care. And it’s already at a point where it’s critical. And so for me, that’s where the public health education comes in.

Because I know that doctors and nurses and everyone else needs to know this stuff. But I feel like there’s already so many people in the field, and there’s a lot of different careers and like education for that population.But I feel like that doesn’t really exist for the general public.

And along with that, I also want to make most if not all of my content to be multilingual. And so, like, I speak two languages, and I’m currently learning a third language. Because I can create whatever I want and I can hope that someone from a community would look at it and read it or whatever. But if I don’t create stuff that actually resonates with them, I might as well just be putting my art in a garbage. Because like, no one’s gonna look at it if they can’t understand it. And that’s where the illustration part comes into. Because I can’t assume that everyone can read. And I also can’t assume that everyone can read at a certain level. And so that is also part of the accessibility of making sure that I can reach as many people as possible. So that’s what I want to do.

That’s really cool. Do you have a sense of what kinds of organizations fund this public health education work for illustrators—would it be a public health governmental agency or are there other sorts of nonprofits? So who’s the employer, I guess?

I have been thinking that something like the CDC or World Health Organization—so things like those could definitely be an avenue. And I think that I would like to be a part of something government-funded just because I know that I could do work there. For something like a nonprofit organization, I feel like I would love to work there as well because I have worked in nonprofits before and that type of work is very fulfilling, just because it’s kind of on the ground, direct impact.

I think maybe my ideal workplace would be a museum somewhere. Likej for example, the Field Museum, I know that they have different exhibits and they work with medical illustrators on things like those. So I would like to do something like that, but I feel like also one of the bigger things that I would want to do would be freelance work, or just like work on my own where, if there is a specific need, I can come in and help. And I have been doing things like those these last couple of years, where, for example, at the Latino Cultural Center, there was a specific need for signs about pollinators. And so I was asked to do that. And I know that I can help with that specific issue right then and there. And so I would love to do freelance stuff like that too, like, if someone needs something, I can do it.

And then something else that I would want to do down the line is to actually make books. Just me, like I’m the author-illustrator or whatever. But it would mostly focus on—I’m not sure if I wanted to be like graphic novels or picture books for a younger audience, just because for preventative medicine to work, I feel like it also needs to start early because it’s really hard to change habits later. So if there were some sort of books where it’s very, very basic, like, “This is how the body works” type of thing, I feel like it would encourage younger audiences to want to know more and to be curious about themselves.

Because when I was younger, I remember that my dad would always get me books about, like, Oh, your body’s changing; what does that mean? Stuff like that? So from very early on, I think I was always really interested in that. Like, I don’t know, I just always thought—I mean, everyone has a body. Everyone has a mind. I think it’s important to know what that even means and to be able to take care of them.

Are you particularly interested still in neuroscience and teaching about that to the general public? Is the brain the organ that you feel like you’re most interested in?

Yeah, so I do really love neuroscience. That’s what I think is maybe my passion, that’s my calling, but I’m also really well-versed and I have a lot of knowledge about general anatomy. So I would love to work with general gross anatomy, because I feel like people would be more interested in learning that first, and it might be easier to digest because neuroscience can be hard.

But if I were to make something I feel like it would be not delving too deep into things. I feel like it’d be moreso the pathologies that come with your brain. Because I feel like that’s the important stuff. So like, you know, when you have, like, a blood clot in your brain, or what does a stroke mean? You know, things like that.Not necessarily like, This is how your brain works in the most detailed way. No, it’s moreso like these are the illnesses that can come with your brain. And that includes mental health.

When you were talking about making work linguistically accessible, but also accessible to people with different levels of literacy—I teach my 161 on health disparities. And one of the things that I thought about when you mentioned neuroscience is the still not fully understood disparity in the rates of Alzheimer’s in the Latino community, relative to others. And there are nonprofits like LAMDA, from what I’ve read, where part of what they’re trying to do is increase health literacy about this—partly because of what you’re saying: if you can identify symptoms early, there are things you can do to slow the progression, or information you can share with caretakers. Is that something that you thought about, the health disparity angle? Like, what are the things that are affecting some communities disproportionately?

Yeah, I think about that all the time.

Yeah, I imagine that’s right up your alley as well.

And that’s also why, actually, for my undergrad, I really liked focusing on DHD, the Disability and Human Development courses, just because for my major [Rehabilitation Sciences], we learned a lot about the US healthcare system. And it’s very important; I’m glad that I took those classes because it is important to know how the healthcare system works and the different interdisciplinary teams and all of that. But that was really, really focused on, I guess, more like the physician view.And I think it’s important for me to know the physician view, so that I can also help patients.

But for my other classes that I took with DHD, a lot of the focus was on, like: yes, this is how the healthcare system works, but also like, where’s it not working? And why?

And that, to me, was the highlight. Because I appreciate parts of the healthcare system here in the US, but I also know that it’s not all encompassing. And there are a lot of people that fall through the cracks. And knowing that, for me is just like, also part of why I want to make my work a lot more diverse. Just because I know that in medical illustration, now, it has been changing the couple of years, but most things are centering lighter-skinned folk.

And it’s just not diverse in terms of outwards appearance. And that also means that it’s not diverse, in terms of how different diseases affect different groups.And that is a really big thing—we actually still don’t have a lot of visualizations for, like—it’s so hard even to find pictures for example of how a third degree burn looks like on someone who has like really dark skin, compared to someone who has like really, really light skin. Like it’s really, really hard to buy different imaging for them.

And that all just kind of falls back into the same thing of like, who’s getting left behind? Because if we can’t tell, like, Oh, yeah, like this is what a stroke looks like in this population, it’s really hard to help. And that is part of the reason why many people fall through the cracks because we just don’t have that diversity yet in the actual clinics.

That sounds like everything I hear when I do this research. I mean, it’s underrepresentation among the physicians themselves, their lack of familiarity with different languages and cultures, but also just different experiences. Do you feel like in the field of medical illustration, in terms of your cohort demographically, is it diverse or does it skew one way or another?

So in my cohort, we’re pretty diverse, and that’s in terms of everything, not just race or ethnicity. It’s also in terms of gender, sexuality, religion—we’re very, very different. And I’m really grateful for that, because from the very beginning, from when we all met, we have all been learning a lot from each other, not only in terms of culture, but also in terms of our skills. Because we grew up in such different environments, we all bring something different to the table. And that is really good for creativity as well, just because since we’re all creating, we basically get the same prompts for things, but we all have a different solution. And so the more diversity that we have in our field, I feel like the more solutions we can come to, when it comes to actually teaching medicine and science.

That does seem really important. Like if you don’t have all those different perspectives, you’re not going to be able to reach all the audiences.

Yeah, exactly.

Are you a tight cohort? Are some of these people the people you did undergrad with? So have you known them for a long time or is it not necessarily that the whole undergrad cohort has just moved in?

I’m actually the only UIC student.

Really?

Yeah. So there’s people from all over the place. Like some of my cohert are from New York, different parts of California, from Texas, from Georgia. We’re from all over the place.

I guess I would have thought that people in your undergrad major were looking into that same career path?

No, no, I was the only one looking into this. Everyone who I studied with in my major, they all wanted to go into either physical therapy or occupational therapy. And then some others wanted to go into speech pathology. I was the only artist in the group.

Were you taking art classes then? Because you said your minors were actually in Disability and Human Development and I guess Life Science Visualization was your art. Is that right?

Yeah.

So is Life Science Visualization a major and were the people in it headed for your track, this Master’s program in Biomedical Visualization?

So that was actually a minor, and it was new. Like my freshman year, they had barely, like, set it up. And so actually the minor has been at UIC about as long as I have.

But I did actually meet some people who were interested in medical illustrations, like, for the first time in my life. I was like, Oh my gosh, like I want to do that too.

But a lot of the people that were taking those classes actually wanted to be physicians. So a lot of the friends that I made there are still continuing their studies to become either like doctors or surgeons and things like those. But it was really interesting to see that, because a really,really good way to study and learn and actually keep that information with you is to draw things out. So like everyone learns differently, but for people that are kinesthetic learners, it really helps a lot more to physically draw something out so that you can see where something is and how it’s connected to other things. So to me it makes sense that a lot of people were in that actually because they wanted to learn that side of things too.

And some of the others that were in those classes just wanted to go into art. A couple others were just taking classes just because they seemed interesting. Some of them were studying computer science.

So that’s really interesting, it’s a brand new minor. Is it housed within biology or within the school of the Arts?

It’s part of Applied Health Sciences.

And any advice to people? I know sometimes new programs can have growing pains and stuff like that, but how was your experience with it and would you recommend it?

It was really good, and I would definitely recommend it. So the classes were relatively new then. I guess at this point they’re not even that new, to be honest, because they’ve been going a couple years. But the faculty that have been together actually really know what they’re doing. So they’re experts in the fields.

Like I took classes with one of the faculty of the Master’s program and so she already knew—it was very basic in terms of, like, the Adobe suites and things like Photoshop and Illustrator and AfterEffects and things like those.

And then some of the other faculty had already been practicing medical illustration for years before they joined us as faculty.

That’s really good to hear. I feel like people may not be aware of this as an option given that it’s so new.

Favorite parts of this field of studies and any challenges or less favorite parts, in terms of, I don’t know, software or, you know, squabbles with your skeleton?

I would say that I like all of it. But the challenging part I would have to say is the anatomy lab. Just because the actual class every first year has to take—-and it has not changed since my professors were in the programs—-it’s basically like you get a full semester, but you really do have to learn like the entire body, like, minus the brain. And that includes every single muscle. All of the blood vessels and like some of the pathophysiology of it as well.

And so the actual class would meet three times a week for like an hour lecture and then a three hour lab. So it was basically like a part time job to be honest, because my class and I, we were in the lab for like 16 hours a week. And that’s like not including the lecture or actual study time outside of the class. So it was definitely a challenge.

Wow. How many credits is of course like that?

Five credit hours.

That is time-consuming.

Yeah. And it was really hard for me just because of my commute. Like, it’s a very far commute to you. So like I have to either take a bus or I have to wait for one of my parents to be able to pick me up from the station. And it’s just—basically it takes me between three and four hours to commute, like, every single day.

Really?

Yeah. And so I was coming into school five days a week for classes, and I would also come in on Saturdays to go over the material for the lab. So I would go into the actual dissection lab and, you know, look at my door and studying. So I was coming in six times a week.

And with 3-4 hours there and back?

Yeah. [I live near O’Hare.]

Yeah, that can be a long, long commute.

Yeah, it is.

And so I, outside of the actual class and the lab, I would also go to my professors’ office hours at least once a week, because I really wanted to make sure I knew the material. And my professors were nice enough to let me—like I was in there, like, three times a week at one point right before exams. So they were all very helpful. So it was a really, really hard class because anatomy is hard and because it took so much time. So it was challenging, but I really liked the experience, because I had never been in an actual cadaver lab before.

So this was my first time just because I had enrolled for my anatomy class in my undergrad to be also in cadaver lab but then the pandemic happened. So I was never actually able to go in person and have that experience. And I was able to do it here, for the Master’s program. And it was really hard and a lot of us cried. But we go through it together. So the good part about that too, is that we’re all a community. And since a lot of us come from different backgrounds, some of my classmates studied anatomy for, like, four years in undergrad and others of us, this was our first time learning it. And so it was also helpful just because we had such a range of knowledge that we could all kind of piggyback off each other when we didn’t know something.

Now in terms of, like, favorite things? I don’t know, I guess you could say it’s maybe like, being able to practice art? Just because I come from a science background and everything that I knew about art was just, like, self-taught. And so coming into this program, I actually wasn’t that confident in my art, to be honest, and I never liked showing anything except for the final product.

But I was able to find a lot more confidence through the program, just because we would do a lot of sketching, and for the illustration techniques classes, for those especially, our assignments were to basically sketch something about anatomy every single week. And then we would get little prompts of like, Oh sketch, like, your favorite fruit or sketch what it feels like to be really happy. Or you know, things like those.

And so that was helpful and we did figure sketching as well. And so just doing it so many hours, I was able to improve really quickly. I think that’s a really good thing about the program’s [way] of, like, learning things. It is fast-paced, but there’s so much material there and resources where you can actually do it. And I feel like the process of learning and practicing can be quicker through the program than if I were to be learning things on my own.

I’m glad they give you a chance to also draw in a more free way because I feel like the precision and technical nature of the drawing you’re doing for your assignments must be—you know, it’s so specific.

Do you feel like you have an art practice that’s just for yourself that you enjoy as well? What do you like to draw when not drawing medical illustrations—other media or other subjects that you like? (And I realized you may not draw for fun now if you’re doing so much of it for school.)

So before this I never drew for fun. But the thing about the classes though is that because they give us these, like, cute little prompts, I don’t have to just—-like, I don’t know how to explain it, because before I was never able to just doodle.Like I couldn’t do it. I would only draw if there was an end goal. And I was the type of person where it had to be perfect. Like every single line, and I didn’t do little sketches— no, none of that. It’s like what I started with how to be perfect the whole way through.

And I’m not like that anymore because of these different sketching prompts and things. And so, now, what I’ve learned to do for fun is to make little comic strips for myself, of like, just random things. It’s almost like journaling, to be honest? Except it’s like little pictures.

I think my funnest thing that I have made a habit of is I’ll ask my sister like, Oh, what’s the word of the day today? And she’ll tell me, and then I’ll doodle it. Like, I’ll make a little comic strip for. And so I wasn’t ever able to do that before but now that I’ve been practicing—and also I feel like that’s a form of well, one I’m learning new words. So that’s cool, and then I’m actually practicing how to visualize the words. So it’s kind of like it’s a two-fold thing.

And I have also gotten more into like—because I before really do a lot more digital art, and now I feel like it’s kind of a mix between digital and traditional, and just pen and paper or pencil and paper. But I feel like that’s also because of my notes. Because I actually even [don’t] have to write things [in words]—like, I do different drawings and things [instead], and these are just like my notes for classes.

Oh, wow. Interesting. I should have asked about that. I’m curious now how you take notes in class, because you have to make visual notes. What is the white that you’re using there?

It’s just a colored pencil.

So it’s a slightly darker paper and so you when you’re making notes, you’re using colored pencils primarily?

Yeah, I love gray paper.

I have never seen gray paper before. It’s actually really beautiful.

I also actually have some art here too.

Oh wow. Look at the shading on that. Did you study figure drawing as part of the program, or are you teaching yourself that?

We did for one class. Like our assignments for one class were to draw different poses and focusing on different parts of the body. And we did one where it was we had to focus on the back. And we also had to show where the different parts of the spinal cord are on the actual picture. So the professor would ask us, like, Oh, where is C1? And T1? So it was good because we were practicing the drawing but we were also still thinking about the anatomy behind it.

Has studying this made you see the world differently in any way? Like, do you feel like it affects how you see either. you know, bodies or just how you see?

I think that studying art in general, it makes you notice things. Like for example, the amount of highlights in different things. Or like, Where’s the darkest shadow? Or like, that contrast is really high. Or, you know, things like those. Or even with, for example, when I’m reading a book, and the text feels too small or it’s too squished together, I’ll think like, They should have made this font bigger. And that’s the graphic design coming in. And I don’t know—I feel like I do see things differently.

Or, for example, for animation classes, when I started taking those and then I’ll like watch something and I’m just—hmm. I wonder what they were thinking of when they made this, or what made them pick this color scheme? Things like those. Like, I’m just like wondering about the process behind things.

But then in the actual real world, I realized that I like to find the highlights in things. I’m just always like, Oh yeah, like if I were to draw something like that’s where the highlight would be.

Interesting. Yeah. So you mean like you’re looking at how highlights fall on people and things around you. Are you someone who likes working with certain media more than others? You mentioned colored pencils. Is that the default for you? Or do you also work with gouache or ink or anything like that?

No, my focus is just pencil and paper. I recently have been using colors just for my notes but for my actual art I prefer just gray— like, black white, gray tones. Like, I do not use color.

When it comes to digital art, that’s different. For digital art, like, it’s just all color.

The other question I like to ask everybody is how does your experience as a Writing Center tutor come into play in your work and study as a medical illustrator? Is there anything that you feel like carries over or transfers?

Yes. I feel honestly for any career that you go to writing is always going to be a really big thing.

For example, for my career, we use writing every single day. And it doesn’t even actually matter what type of really niche fields you go into in the career, because we always have to do like, for example, script writing. And we always have to be able to get our ideas across using the least amount of words, but for it to still be clear.

And even for just the Master’s, not even going on into the career, we have to do a whole research project. And we need to be well-versed in our writing skills. And not everyone in my program is confident in their writing skills. And actually many of them are like, I hate writing.

And it’s also scientific writing. And so that is different too. And I feel like my entire time when I was a tutor, I was always being in a situation where I learned how to pick out, for example, strengths in writing, or weaknesses. Or I have picked up skills on how to help people, you know, brainstorm. Or, like, what part of this do I not like—and ask the question, why? And that has been helpful for my classmates too, because if I want to help them with their writing, if I can just read something, I can immediately pose at least one or two questions of what about this works or what about this doesn’t work?

And so, the writing tutor has not ever left! I am still like that even now, and I know it’s going to be really helpful for when I go out into the career, because, just like I said, not everyone likes writing. But it’s super important for getting your message across, and that’s through and through, it doesn’t matter what career you go into—I feel like because you have to be able to understand the messages coming in and also be able to translate them out.

It’s such a good point, because I feel like some people might go into medical illustration thinking that someone else does the writing, I just illustrate. But in fact, because your illustrations are so central to conveying information, they’re not supplemental to the message—they are deeply embedded in it. I imagine you have to be part of designing the entire message, including the language that accompanies it, right? And, like you said, even the storyboarding, you have to think about the sequencing of information. And so you have to be a strong writer?

Yeah.

And I think it’s much harder to explain something complex simply than to say it in your disciplinary jargon, right? Like, to make it accessible to a general reader means you have to have a really deep understanding of it, but also have real economy of language.

Do you feel like that sets you apart a little bit, in that you do have confidence and facility in writing, and you’ve been reading so many different kinds of writing from so many different disciplines as a tutor?

I feel like it probably does set me apart a bit. I think that, career-wise, I could definitely use that—-like, if I wanted to go into scriptwriting or storyboarding, that would be a huge plus in the eyes of the employers, because I know how to do this. Because scriptwriting is different.

So scriptwriting is a different specialty? And storyboarding is also a different specialty?

Yeah, but I feel like I would probably stand out in terms of that. I think that, for now, I’m just glad that I have this experience because I can be a resource for everyone else that I work with. And in our class the other day— it’s like a class that we have to take for our research—our professors said, We’re going to do exercise in APA stuff. And she divided us up into groups, and everyone in my group was just like, Yay! We got the Writing Center girl!

It’s interesting that you say that this gives you some flexibility in terms of what path you take. I think when you have facility both with words and pictures, it also enables you to do what you’re talking about, be an author of your own book, from beginning to end and really think synergetically. I’m really excited to see what you do.

Thanks. Me too.

My last questions normally are: What advice would you give tutors interested to pursue a similar graduate path? It sounds like there is a minor now, that would do them a service to study it. Is there anything else you’d recommend to them?

Yes, I would say that they should reach out to people. It doesn’t matter if you know them or not, if you can find their email—especially if they’re UIC faculty. Because for the students in this university specifically, they’re at a really, really big advantage that we have the biggest program.

So for example, when I was a freshman, I reached out to one of the faculty. I just sent an email and I was like, I’m really interested in this career, can you tell me more about it? And all of the faculty here are more than happy to talk with anyone. Like I’ve had a couple of friends who have also expressed interest, and I was like, Yeah, shoot them an email. And immediate response. Like, Yes, let’s talk about it.

Yeah, so I think that for any students that are at UIC now, if there’s an interest—and it doesn’t have to be medical illustration; it can be other paths like that, if they’re interested in just science and art, because like scientific illustration is also a thing—and so like, just kind of seeing what they’re interested in and reaching out, asking. And it doesn’t even have to be anyone at UIC. Like, if they come across someone who’s a medical illustrator, it doesn’t hurt to ask questions. And I think it’s good to try to figure out if, you know, that is something that you do want to pursue early on. And the more information that you have about a specific career, the better. Just learn a little bit more, like, here and there. And then maybe it’s not for you, I mean, you know, but at least you asked, and now you know more about it, and maybe it’ll help you find what career path you do want to go into.

That’d be my advice is just reach out to anyone in the field that you’re interested and just be like, I’m interested in this; could you tell me more about it or do you know someone who could tell me more?

I think that’s really good advice. I also am a big fan of informational interviews, which is what you’re talking about. If someone wanted to speak to you about your experience directly,would you be amenable to them talking to you? What’s the best way for a tutor to reach you if curious?

Yes, of course. I’m on LinkedIn, it’s just my name: https://www.linkedin.com/in/eyzel-torres-239a7b225

Is there anything you wish you could go back and tell your undergrad self?

I ask because it can be a hard thing, making that postgrad transition—are there any mental health or self care things you’ve done to help yourself survive the move? For you, it might have been more seamless because you knew what you wanted to study and you were pre-admitted. So you didn’t have to go through a big job search the minute you got out of undergrad, but I imagine there’s challenges we all face along the way. I always have felt, Eyzel, that you have a real equanimity, a poise and grace about you. Like, you always are calm and you have a wisdom about you that I admire. How do you maintain a sense of calm and grace and poise through, you know, for example, 15 hours worth of anatomy? I’m sure there’s stress in your life.

I would honestly say—okay, well, when you asked about being able to tell my undergrad self advice? I would say, not to be so confident in my skills and knowledge yet, and to start practicing. Start practicing early. Because, since I did know that I was going to be a part of the program, and since I did know that I was not as good at art as I was in science. I would have said: practice your art. That’s what I would have told myself, so that I can be at a point where I felt more confident early on. And it’s okay, because, you know, this is just the path I took, and like, that’s fine. I didn’t have to be an expert in anything. But I also knew I had to learn anatomy and I was like, That’s a problem for, like, grad school Eyzel. So I never paid attention in things that I knew were gonna help me. I was always, like, No, I’ll learn it later. So I kept putting it off.

So: advice for someone who knows what they want to do, and doesn’t have a plan B would be practice little by little so that it doesn’t hit you like slam dunk later!

Particularly areas where you know that maybe you have less practice—like, target those and give yourself a little remedial practice with it?

Yeah, so I would advise anyone who is, like, 110% sure they know what they want to do. And even if they’re not, you know: practice, little by little. Try to learn little things here and there. And if there’s something about that field of study that you know you don’t like but you have to do, try to ease into it. Or if you know you don’t like it and you know you don’t have to do it: well, now you know you don’t want to go into that part of the field and you can focus on something else.

In terms of stress, I would say: cry. Like, cry. Just cry. Like if you feel overwhelmed, cry. And talk to someone about it. Like if you feel like you don’t want to ride the train today, talk to someone that you feel comfortable with. Because that’s a part of mental health. Like, you can’t bottle everything up and expect to be okay. And you don’t have to talk to everyone and you don’t have to tell them everything either. Like, it’s okay to not express everything that you feel. But for the things that are overwhelming, the things that you know are stressing you out, the things that you’re scared about even—like, if you don’t want to talk to someone, write it down. If you don’t want to write it, record yourself. Do a voice note. Or draw how you feel. You know, just something to actually get that stress out.

And I know that a lot of people see crying as a weakness, but actually when you cry, you do get rid of a lot of things that are there. Like physically. I mean, the tears, the physical tears, are carrying chemicals that are making you feel that. Yeah, and you cry, and now you feel better! It doesn’t work all the time, obviously; sometimes you cry and you still don’t feel good. But for the things that are, you know, not like these big major defeats in life, it’s okay to cry about them.

And if you have to schedule yourself a five minute cry every single day, if that works, then that works, you know? And, like, just being able to express that and not having so much stress or anger or anxiety or sadness or whatever that feeling is—because if you don’t do anything about it, it makes you feel like you’re just tightening up, you know? And that’s not healthy, by any means. And yeah, I feel like that would be, in terms of the stressful things, my advice.

That’s really helpful—it’s interesting when you talk about the actual physical mechanism of crying has an adaptive function. In my health disparities class, we talk all the time about how chronic stress elevates cortisol levels and that stress hormones can be measured in the saliva and all that. But I never knew if it actually could be measured in the tears as well. And if the tears were sort of helping eliminate some of that build up.

There’s actually this study that looked at different tears—like tears from anger or happiness or sadness, and they had a different chemical makeup.

Are you living at home right now? Are you still doing the crazy commute?

Yeah.

How is that working for you?

It’s hard. Yeah.

Do you live with your siblings and parents?

Yeah, my parents and two of my siblings. My two younger siblings. I have two older and two younger siblings.

I feel like you have the maturity of an older sibling and someone who has been involved in caretaking for other people. Is it a good supportive environment—is your family supportive of the path that you’ve chosen for your career?

So in my family, I’m the first one to have ever graduated from college. And also the first one to attend like anything past that. And I know that my parents are really proud of me for that. And they like to talk about it with other family, whenever something comes up, they’re just Oh, yes, but she’s in school and we’re so proud of her for it. And I really appreciate that they talk about it—because it is a really big thing. This is huge. Having to commute so much and having to navigate a system where I had no idea about anything. Like when I started, I didn’t even know what a major was—I 100% like quite literally did not know what a major was.

I just knew that I liked biology. And when I was asked in high school, what I was gonna study, I was like, I don’t know, I like biology and they’re like, Okay, write that. But I didn’t know what that meant. And so having to go through all of that—and it really was on my own, because I couldn’t really talk about this with anyone. Like my older siblings didn’t even graduate from high school, which is like okay, it’s just the path that they’re on. And then the one after, so she started college, but there was just a lot going on financially and she just couldn’t continue. And so then I was the next one. And it was a lot of pressure just because I had seen a lot of things growing up. And I knew that education was something that my parents really, really believed would get us up and higher and not have to deal with all the struggles of just like our life. And like my mom always wanted to go to college, same with my dad, but they were never able to. And so for me it was the biggest driving factor in my life. It was just like I’m the one that’s going to, like, buy my parents a house; I’m the one that’s going to be able to financially support my siblings. Like, I’m the one that’s going to do this, this and that. And I think that was the biggest stress in my life during those four years and even today—that still has not left. But I feel like that was the thing that really made me cry more than anything, because it’s just a really, really big weight on my shoulders. It always has been. And it’s hard. Like it’s just hard. But everyone has always been so supportive of it. Like if I was stressing out about like, Oh, I want to go and get my Master’s but I don’t know how to pay for it. I would cry about that all the time. I’d be like, This is my dream, but I know we don’t have money. And my parents would be like, Oh, don’t worry about that. Like you’re already in, we can figure out the money later, we can take out loans, we can look for scholarships. And I feel like that was maybe one of the biggest things, that like they were able to just comfort me, to like sit there with me and like hug me and just be like, it’ll work out, like don’t worry about it. Because I am the type of person who— I use my brain, not my heart. And so for me I’m like logistically, this doesn’t make sense. Like it’s not gonna happen.

But for them, they’re like: No. We will carry you and your dreams. Like, we’re not gonna force you to pay rent, because we know you have to pay for school. Or like, we’ll cook for you. Or we’ll take you to the train station—because like if they didn’t take me to the train station, my commute would be 45 minutes longer. And so like they do all of those little things—-like it’s not just like words and it’s not just like them being physically there. Like they also know how tough it is for me to actually even get here, you know. That’s a big thing. Like if, if I didn’t have them driving me to the train station, like I probably wouldn’t even be here. Like, that’s just a fact.

And same with my siblings. Like, they’ll be able to just sit there and listen. Like if I have to complain about something like, Oh, like the worst thing happened on the train—because there’s a lot of things that happen on the train, as I’m sure you know—they’re just like, That sucks. Well, you’re safe and you’re home, so it’s okay. And I’m just like, Yeah, you’re right. That does count for a lot. So they comfort me with words and actions and it’s nice to just be able to go home and lay down.

I wake up really early to get here, and then I go home late. Last semester I wasn’t at my house, like, ever. I was on campus for 12 hours a day. And so this semester is a lot easier just because I don’t have the anatomy class. That was the hardest class because of the time stuff. But I still have to get up early and get home late. And so I always sleep on the train. But now I feel safer about it—because now my brother commutes with me. And they take care of me. So they know, like, Oh, Eyzel’s tired. So like I’m not gonna bother her when on the train. So even companionship. They’re all really awesome. Like, I am really lucky to have them as a family.

What you’ve undertaken on behalf of not just yourself but the whole family as a first generation college student—it’s huge. I can relate. I also was very reluctant to take on graduate school because I felt like, How would I pay for that? How did you end up funding your master’s program? Did you get a scholarship?

For my first semester I applied to a fee waiver thing that the Graduate College offers. And so I was able to get that and I didn’t have to pay for the first semester.

And then for the fall and spring, I took out a loan, because I didn’t have time to do scholarships or anything like that, just because I had just graduated and it was my last semester and I had a lot going on.

And my last semester I was also doing a lot of social justice work, and it took so much time. I’m really really grateful that I did all of that because, you know, I love doing things like those, but it did take a lot of time that I couldn’t use looking for scholarships or applying for things.

And then for my second year, I spoke with the director of the program about my finances. And they told me that they’re opening up a new fellowship type thing. So I’m gonna be applying to three fellowships. And if I don’t get any of them and I’m just gonna take out another loan because at this point, like, you know what’s 25K more?

Yeah. Were you someone who was interested in a TAship, but they just had limited ones?

Oh no, I can’t do a TAship because of the commute. Like, there’s just—I can’t do it.

It’s too much work for me. Like, I would love to be a TA. But I know my limits and I don’t want to stress myself out.

That makes sense. As someone who has worked as a tutor, you mentioned that a lot of the professors you have do have a practice as medical illustrator and also teach. Are you interested in the possibility of teaching down the road?

Oh, yeah. I would love to. I love higher education. I would LOVE to be a professor. And I know that at some point down the road, I want to get a PhD. And there currently isn’t a doctorate program for medical illustration, but I actually know of some folks who are trying to get that to happen. And so maybe, you know, in 20 years or something, when I’m already practicing, they’ll open up, you know, a whole new PhD, and I would love to do that.

But otherwise, I would love to get a PhD in something that has to do with public health, education and things like those, because I know that at UIC, there’s a PhD for teaching medicine, which could also be something that I can do. And like there’s a whole bunch of things—but yeah, like I know, I’m not done with studying.

Well, I’m really appreciative of your time talking. What is making you happy these days? You have very, very long days. Is there anything that is just purely joyful for you these days—anything that just helps you decompress?

Yes. Playing with my cats and drinking tea.

What kind of tea do you like to drink?

All kinds, but chamomile. Also Earl Gray.

You mentioned maybe doing as a research project something about teas that have a medicinal property as well?

Yeah. I’m pretty sure that’s what I want to do.

Is there anything you think I should have asked you or things that you want to share with fellow tutors?

I already said this, but I want to emphasize that it’s okay to ask for help. And that includes the whole spiel about crying and talking. But even the little things. It’s okay to ask. Like, if you don’t know how to find a classroom in BSB, ask someone. That is okay. You do not need to feel embarrassed about not knowing something because no one knows everything. If you don’t know something that feels like it’s small to you, but you can’t figure it out, just ask someone. You know, it doesn’t hurt to ask; the worst thing that could happen if they just don’t answer you, and you ask someone else.

And I think that professors and faculty especially are a really good resource because they’re usually the ones that have been here the longest and they know, you know, what’s what, and who knows what. You know, where can I find work? Or where can I find an internship? Or you know, anything like that. So, you know, just professors and faculty are always really good to ask questions. And honestly, even if you feel like you know the answer, but you would like a second opinion, or you just want to be 100% sure that’s the answer—it’s good to ask.