Christopher Nevarez Azdar, Writing Center Tutor Alumni Profile

11/15/23 Interview with UIC Writing Center Tutor ’20 alumna, Christopher Nevarez Azdar

11/15/23 Interview with UIC Writing Center Tutor ‘20 alumna, Christopher Nevarez Azdar

- Your pronouns: he/him

- Your major/s/minors at UIC: double major Political Science & Spanish

What term did you take 222, with whom, and what years did you work as staff tutor? Second semester 1st year spring 2017 with Gregor, 482 S2020 with Charitianne; tutored 7 terms, F2017—S20 - Year of graduation from UIC and undergrad degrees (BA/BS?): BA 2020 Spring

- Year of graduation from law school: JD May 2024 Chicago-Kent College of Law

- Current job [as of 11/24, post-interview] : Cook County Assistant Public Defender

What is law school like right now?

I’m wrapping up my last year and I’m taking a lot of core classes that’ll be on the bar. And I’m getting a lot of hands-on experience in my two positions. I work at an immigration firm downtown. And because my main focus is criminal law, I specifically work with clients that come in seeking to adjust their status through visa, green card, asylum, any sort of immigration relief they might be seeking, or Cancellation of Removal. So that means they have an order of deportation for us to fight that. But [they also] have a prior arrest or a prior conviction on their record. And it really does vary. It could be something as minor as a bunch of traffic tickets to anything that might be more major that might bar them from adjusting their status here in the US. So that’s what I do there. I do legal research specific to that.

Is that an internship or a paid position?

Paid. So I’m a law clerk there. And I’m also a law clerk at the CK Law Group, which is a criminal defense clinic at school. And so there we work with a supervising attorney, who’s also a professor there. And we handle real cases. So we have clients that come in and, as a group, we are students that are focused on criminal defense and we essentially assist the attorney in everything imaginable. So we do jail visits with clients. We do interviews, collect evidence, review discoveries, any evidence that might be used during any potential proceedings. And we handle a lot of federal cases for that—a lot of federal criminal cases here in downtown.

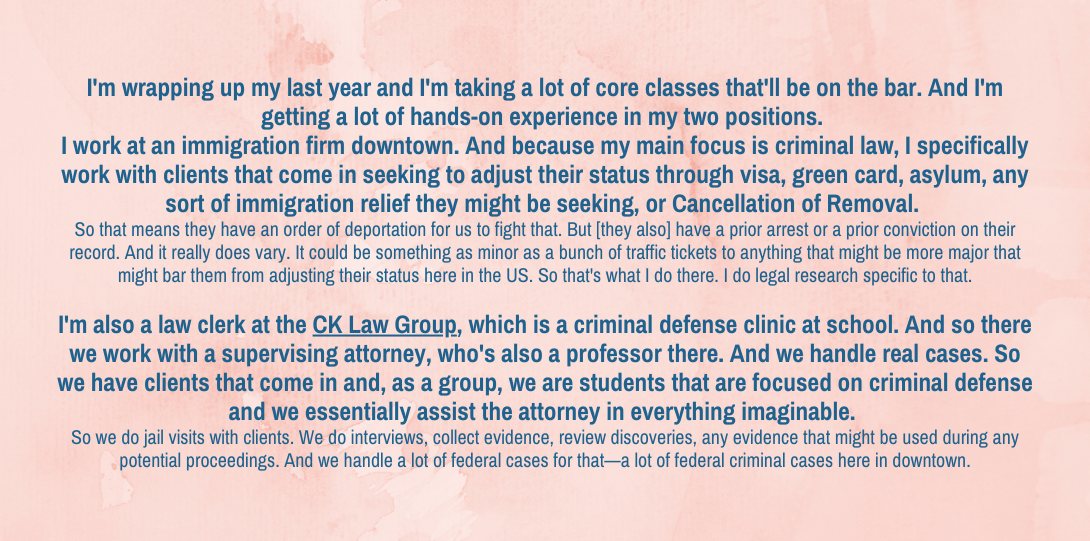

Are these positions in areas that you want to pursue in an ongoing way—do they reflect the kind of law you want to practice?

Yeah, so I knew I wanted to do criminal defense from the very beginning, even before I applied for law school. So the clinic I’ve been doing since my second semester first year, so that would be spring of 2022. So I’ve done it for a few semesters now. And that’s only reaffirmed my interest in criminal defense.

And then the immigration law position I took originally because I simply wanted a longterm position, a job that was flexible that was paid, that I can do during the school year. And I’m an immigrant myself, so I thought okay, let me take this opportunity. One of the attorneys there I had worked with previously and so there was a connection right away. She offered me a position, I took it, and as I’ve been there, I’ve seen the intersection of immigration law and criminal law. And it opened up my interest to possibly doing some pro bono work in the future in immigration law specifically— helping clients fill out forms or anything that isn’t crazy time-intensive but that they don’t need to be paying an attorney outrageous amounts of money to do for them or to review. So it’s opened my eyes to that, doing a lot of that work pro bono, doing it for free for clients.

How did you get from undergrad to law school, what was that path like? And is there anything that you wish you’d known beforehand—any advice you’d give to others on the prelaw path?

I’ll start with how I got there. So I finished, like I said, in spring of 2020, and before the pandemic hit, I had already planned to take a year off. And then it so that year on came as a blessing where I wasn’t starting my first year of law school remotely, because a lot of my peers that did that really did struggle to make that adjustment. I mean, law school is intense. It’s a lot of reading and there’s so much benefit to being in a classroom setting and to being able to interact with your peers where you’re not staring at turned-off cameras and looking at my muted screens.

So during that year off, I actually worked as a census and voter engagement fellow. I did a lot of raising awareness and educating folks on the 2020 census. And then voter engagement—making sure that people were voting, registering to vote, using the absentee ballot option. And so that was a really cool experience. But I don’t know if it necessarily . . . .Obviously, it helped my application in the sense that I did some work like that, but I think a lot of people that are interested in law school have a misconception that you need to do certain things before applying for law school so that law schools think that you’re ready to go.

And what I mean by that is I have a lot of friends who are in med school. So the example for them is they do have classes that they are required to take to be prepared for the MCAT which is the entrance exam that they have, like they need to take their Orgos, they need to take their Chems, they need to take their Bios, right, and so there is more of a set plan for them.

For law school, it truly is a free-for-all. It is an open invitation for people to apply with every sort of background you could ever imagine. Because the thought is it’s like a marketplace of ideas, right? When a client comes to you and presents you with whatever issue they might have, then you want to be able to anticipate every potential direction or angle that any other attorney might approach it with, because you’re going to have another attorney as your adversary on the other side. So you need to try to anticipate every objection they might make, any way they might use evidence against you or for their client, and because of that, you don’t want all English majors and you don’t want all Poli Sci majors. And I say that as a Poli Sci major. I thought: if I do Poli Sci, it will feed in, right? But then you get to law school and I have classmates that are Engineering majors, that were premed in undergrad, that did Teaching, that did every single degree you could imagine. They come in with that.

Or a lot of them come in later— the average age of my class our first year was 27 years old. So it’s all these professionals who did something else for a few years. And then the benefit of that is you have this pool of individuals that come and approach a problem in very different ways.

I have some engineering friends—they’re very methodical. A client could come and tell something to me, a Poli Sci/Spanish major that worked at the Writing Center, and right next to me it could be my engineering classmate. They’re in law school. We’re both lawyers. We hear the same client and we’re going to process the information in a totally different way and come at it with a different argument, we’re going to think of different laws or regulations that might apply to the problem.

So because of that law schools like to invite students with a diverse educational background, because then your first year, especially when you’re in sections, and you have every class with the same group of kids, there’s a lot of back and forth discussions and presenting arguments and ideas. You start opening your own mind to think, Oh, I didn’t think about that at all. . . . Someone that did something very different or that taught for a few years or that traveled the world for a year, again, they’re coming in with all these perspectives, and that’s very beneficial. It’s kind of like here at the Writing Center. We want tutors that come with different experiences, because they’re going to meet writers with different experiences. You’re going to want attorneys that come with different experiences because they’re meeting clients with different experiences. Because not every client is coming to them having studied English or Poli Sci, and in reality, they’re coming in with any number of experiences and you want to have been exposed to that from your peers.

So that’s what I tell everyone that’s even mentioned that they might think about law school, and they’re like, But I don’t think I’m ready. They’ll say, Oh, but I’ve never worked at a law firm. Or I’ve never had an internship with a job or I didn’t study poli sci or English or any of that. And I tell them: So what? Like I’m saying, if anything, if you come with a different perspective, you’re going to stand out because a majority of applicants are going to be English or Poli Sci majors, and that will make you stand out because you’re coming at it with a different mindset, a different way of processing information. And so I encourage people all the time. I’m like, If you’re thinking about it, do it.

The only thing that I do suggest as not a prereq but as an undergrad is taking classes where writing and reading is a big component. And again, that doesn’t have to come from just English and Poli Sci class.That can come from a lot of other classes. There are some hard science classes where you’re reading a lot of articles and doing research. And so the research aspect will be helpful. It’s going to just actually prepare you for the load that might hit you when you start your first year and you’re like, Okay, I have a lot of reading to do. So it won’t be as big of a shock.

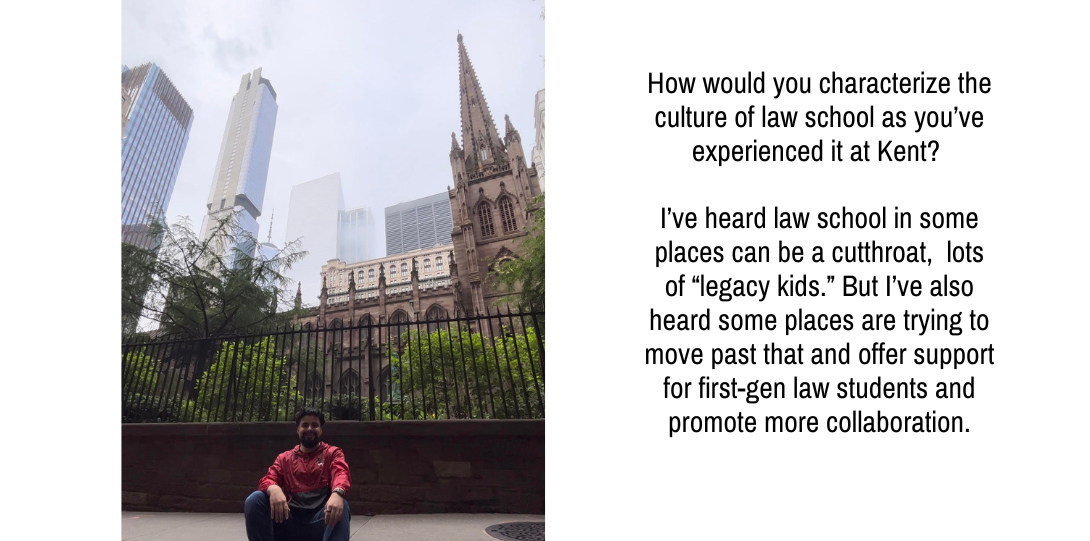

How would you characterize the culture of law school as you’ve experienced it at Kent? I’ve heard law school in some places can be a cutthroat, competitive atmosphere, lots of “legacy kids” whose parents were lawyers. But I’ve also heard some places are trying to move past that and offer support for first-gen law students and promote more collaboration.

So I would definitely agree on the legacy point. Some of my peers, for example, their dad’s a judge, or they’re the fifth lawyer in their family. So there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that at all, actually, and I don’t ever question their own merits on getting into law school, but that does mean that there’s a very different perspective coming in, right? When you’re coming in, we’re being advised, for example, in our first year writing classes to not allow anybody to read what we write. We’re told that it can only strictly be read by our TA and by our professors. Because the idea is they truly do not want anybody else’s input. Because Chicago Kent prides itself in having the best writing program in Illinois. And that’s above Northwestern or UChicago, which are top 14. I thought it was just like, Oh, they just say that, but then you talk to employers and there is actually this sense that [Kent] does produce strong legal writers because we have a very set process of “this is how you structure an argument.” And because of that, they don’t want all these thoughts coming in. And I only say all that because I remember being in the class and being told by the professor, “I know some of you have attorneys in your family. And you might be tempted to go to them so that they can give you advice.” She was like, “But I truly tell you, they’re gonna give you great advice and great writing tips, but it’s not going to help you figure out this system. You need to figure it out for yourself.” But I sat there and I thought, like, No, I don’t. I don’t have lawyers that I can ask them to read this paper for me. Then I remembered that my friend that was sitting next to me, her mom’s an attorney and I was like, Okay, well, she’s talking to her. So there is that part of it.

I do think though that Chicago Kent does have good support systems. We have a First Generation Law Student Board. And I was a mentor for that. So in my second and third year, I worked with a student that was a year below. We just literally meet up, we talk about some of the struggles. Law school can be cutthroat in a lot of places. I don’t think it’s cutthroat in Chicago Kent. I truly think that everyone is there to support each other. The thought is: we’re all here. We’re all going to graduate. Let’s try to learn as best as possible to be the best attorneys we can.

So there’s a big culture of sharing outlines. And there’s nothing actually wrong with that. Sometimes when people hear that, it sounds like cheating if you don’t understand. But there’s nothing wrong with sharing outlines. So very quickly whenever I meet someone, I’ll ask them, Who are your professors? Would you like an outline? And I happily send them outlines because people did that for me as well. So then I was able to use that to help me study and prepare for finals, because as in most law schools, the only grade is the final grade. And that can be very stressful. Your first year, the only grade that you’re getting for every class is your final grade, the final exam, a three or four hour exam, and it’s on a bell curve. So out of 80 kids, there’s like five A’s that are going out. And there’s like 10 to 15 A minuses. A big chunk gets the Bs.

Again, there’s a good culture, I do find that support, and then also I’m part of the National Muslim Law Student Association, which helps oversee all those individual Muslim Law Student Association from schools all across the country. And because the Muslim law community is very small, but it’s growing, we do our best to support each other as well in that way. There are referral systems and we truly try to support each other in any way we can. So I think that makes the legacy issue and all that seem less of a problem or a stress coming in.

What’s your favorite thing and most challenging thing so far about law school?

My favorite thing is being able to take all the classes I did for litigation.Most people don’t know that a great majority of attorneys never set foot in a courtroom. We have this perception that attorneys are in and out the courtroom, that’s what we get from TV shows, but a great majority of attorneys never step foot in a court. I remember meeting an attorney before I started law school and she told me— it was a joke, but it was also actually true— she said that she had been practicing for 30 years at that point and had only been inside of a courtroom twice: when she got sworn in as an attorney and when she got divorced.

I want to do litigation, which is a small group of attorneys that are in the courtroom, that are litigating, that are arguing things in court. So what I have found best is the experience of taking all the litigation classes I’ve taken at Kent. All of them are taught by retired judges. I actually literally came from a final trial today, where we put on trials and there’s a judge that’s our professor and they rule the same way that they would if it was an actual courtroom. And so you really do go through the motions of arguing everything, of bringing in students as witnesses or presenting evidence, of getting that trial experience. And Chicago Kent is a top trial school, I think it’s like number four, or something like that, in the country for its trial team, individuals that are trained for going to court. So it’s been my favorite thing—being able to learn and get feedback from a variety of judges. Because as attorneys and as individuals, we all have different approaches like I was saying earlier, so being able to present in front of all these judges helps us refine our skills. Because if we go: Okay, a majority of the judges told me that I should fix this, they’re probably right, if I’m hearing this across the board. But then when you hear a difference from all of them on a different issue, then you go: Okay, it’s a style thing. They all have their own style, that’s cool. That’s not my style. I have my own style, and I’m gonna implement it. That’s been my favorite thing.

My least favorite thing is some of the classes that I have to take for the bar that are not particularly interesting. But I take them for the sake of having a general knowledge of them so that I can pass the bar and then when I’m in practice—- I think I said this earlier, too, but like, I don’t think lawyers are like doctors at all. But again, there’s a lot of overlapping themes, like I said earlier about when individuals come to you for the first time they’re probably at the worst time in their life, financially. So, like doctors, our goal is to stop the bleeding and find the healing. Right? That’s the goal. But I’m saying all that because I understand even though I hate taking some of the classes, I’m not a big fan, I understand the benefit of it. And that’s, for example, where you have doctors that are specialized in heart surgery, for example. But you would want them to have a general sense so that when you come to a doctor there . . . when you tell them that your ankle hurts, they’re not going to know necessarily exactly what to do, but they’re going to have enough knowledge to start flagging certain issues, ask you certain questions, and then from there, redirect you to the right doctor. So the same thing with attorneys, I understand the value of taking these classes because even though they’re not my area of expertise, or what I want to do, as a lawyer, people in the future and even now come to me with legal questions all the time. AndI’m like, Okay, from what you’re saying it sounds like you have an issue with a contract and it’s this specific thing. So let me send you to the right person. So I understand that it helps us filter and redirect people so that they’re not aimlessly searching for the right attorney. But that doesn’t mean that the classes are any fun.

This is a naive question about law school, but are you also allowed to specialize in the areas of law that you hope to focus on? I know medical students have a residency where they specialize after med school, but do you get specialize during law school?

All law schools essentially have the same theme of there are a number of classes that you take your first year, everyone takes them— criminal law, property, contract law, maybe constitutional law, there are these basics, right? But then after that you truly do get to start picking which classes you want to take. Some students take the approach like I did, where we know what we want to do, so we started narrowing down. I took every criminal law class, every criminal procedure class, every litigation class. And then I added a few other classes that were important for the bar. And then other students truly do take a range of classes.

It’s kind of like in undergrad where a lot of kids have their major picked out right from the beginning, so they start taking those classes. And then others, they might have a major but they still take classes outside their major, or they might change majors, or they don’t declare until later on.

You can defer specializing if you’re unsure.

Or you don’t have to specialize at all. Like there’s no such thing as specializing in law school. There’re no majors in law. Kent does have this program I’m in, the criminal defense certificate program. All that literally means is they’re gonna give me a piece of paper that says I did a certain amount of classes. But it truly doesn’t hold any weight in reality. What it does though is gave me a suggested path that I took in two semesters.

But then we have our summers off. We have a semester system at Kent —like at UIC, 15 weeks. So that means we have a whole summer off. And during that summer is where we begin to narrow down even more: where you pick a place that you think you are probably interested in, and you work at a firm that does a law that you’re interested in, and you start gaining experience. Then your second summer you keep narrowing down. And then ideally that lands you a position right after where you’re invited to come back as an associate or as a full time attorney. So yeah, there’s no major necessarily, you’re not declaring anything, but people do start narrowing down sometimes right from the beginning. Yeah, there’s very few people that graduate with no idea of what they want. Usually it’s like, I know what I want to do or I have an interest in these two areas.

How did you know so clearly what kind of law you wanted to practice?

I did a class in high school, a law class in high school with an attorney who taught it and she did a mock trial. And I was one of the attorneys and I loved it. Like I was dreaming about the case throughout in preparation, right? Like absolutely loved it, a murder case, actually. So a lot of my peers were the jury, and then after that, after that trial, my teacher asked me if I had ever thought about going to law school. And I was like, No. . . .At that point, I was volunteering at a hospital. I thought I wanted to be a doctor. And she was like, Oh, like you seem very comfortable speaking. You seem like maybe you’d be good at being a litigator, at being a trial attorney. And she was like, You should consider it. And I was like, Okay, cool. So then, later that year, she invited me to visit a courthouse on a field trip with others. So I went to the Cook County courtroom.

And so I went there, we sat there, and a lot of the other students were so bored, because they thought it was gonna be like Judge Judy. I was sitting there and I was listening and—I didn’t understand half of what was going on, because it’s all these attorneys with all this jargon—but I’m sitting there and I’m like, I’m so intrigued by the process. And I sat there. And then there was a panel of judges and attorneys after we saw some proceedings, and we got to ask some questions. And at that point, I was like, This is what I want to do.

Then after that, I went to undergrad, did poli sci all, that good stuff.

But I knew very early on that I wanted to be a litigator. And then watching shows on criminal cases and criminal documentaries, and I was like, You know what? Let me do criminal law specifically and that’s how I narrowed it, and I knew before starting, that’s what I wanted to do.

When you say litigator, do people tend to know if they want to be prosecutor or defense? Are those two different temperaments? Do you kind of know—or as a litigator, can you do either?

I’ll clarify this: a litigator isn’t just defense or prosecutor; that would be for criminal cases. For example, if you sue someone, for civil matters, it would be plaintiff and defense. It’s slightly different titles. They’re also litigators. Like anybody that is in a courtroom regularly is a litigator.

Right. Since you mentioned criminal is your interest—do you know what side of that…?

Defense. 100%.

Am I right that those are different kinds of personalities?

Yeah, for sure. And I say that loving my peers, my classmates, my close friends that are going to be on the prosecution side. But I know I want to do defense.

What attracts you to defense? How would characterize those who choose defense versus prosecution?

So there’s a wave of progressive prosecution that I find very valuable, of individuals that want to be prosecutors, but that are wanting to be prosecutors to use their discretion to not incarcerate everyone. I very much appreciate that.

But I want to be on the defense side because my philosophy is— and I really decided this when I thought about it, where I thought, Could I more easily sleep at night knowing that I prosecuted an innocent person, and now they’re sitting in prison or in jail, or that I defended a guilty person and now they’re out and about? And I 100% can always say that I can more easily live with myself morally defending someone that I know committed a crime than prosecuting someone that I think is innocent. And because of that, I know which side I could easily move toward.

Then people will naturally ask like, well, what if they’re guilty? How do you defend someone if they’re guilty? And that’s a very good question. And I think people have the misconception that defense attorneys are there to always say, My guy’s innocent. That we’re there to say, My guy didn’t do it, even when my guy clearly did do it, right? Instead, the thought is: if we have a system, where the state. whether it’s your state government or the federal government, is seeking to deprive an individual of their life, in some cases with the death penalty, of their liberty, or also their money, right, because you can be fined in criminal cases—if the government with all of its resources, all of its might is seeking to deprive someone of that, no matter what the person may have done, they deserve an individual that’s trained to stand there and tell the government: Prove it. Defense attorneys ultimately are a filter to make sure that the government fulfills its burden of proving an individual did something and committed a violation of the crime before depriving them of anything.

Some people will think, Well, what if it’s, like, a mass murderer?— they always think of the most extreme case— and I understand the sentiment, but then where do you draw the line? If you start saying that certain people don’t deserve an attorney and don’t deserve someone to have a check on the government? Everyone deserves that. Because ultimately, like I said, in a lot of cases, we have clients and they come in where we know they did it. They don’t need to tell us. We see the video. The government sends us the information. We see the evidence. Our job is to simply stand there and say Prove it.

And that’s why I’m very attracted to the defense side, because it’s not here to just defend people that might have done horrible things. It truly is like a check in saying, like, Cool. If you’re going to move forward and deprive this individual of whatever it is you’re seeking to deprive them of, prove it. It’s simply a check on the government. I’ve always been very much for checking whatever party has all the power, and making sure that there’s some due process and rights are protected.

There’s also an argument to be made that we know there’s vast disparities in who gets incarcerated and who doesn’t—that there are huge racial and economic inequities in sentencing that the system isn’t acknowledging. Seems like you need a counterbalance that.

Exactly. Like, you need someone to be there to check any potential judges or jurors that might have a bias that would then cause someone to lose their life or their liberty. We need that check. And I love the idea of being that check. Of being one of the actors there to make sure the government does their job. It’s ultimately their job. It’s their burden. The government has the burden of proof to prove someone is guilty of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt.The defense side is not compelled to prove anything. Like, the defense does not need to bring in evidence, it does not need to bring in witnesses, it does not need to do anything else if it doesn’t want to. It could simply say, prove it, and if you prove it, now I’m gonna respond, but if you don’t prove it, then it ends there. If you can’t prove your side, we have no reason to respond. And I think that’s the important part of the system. And that’s why I err defense.

You mentioned working in immigration law. Are there certain communities that you hope to serve particularly in your capacity as a lawyer?

I really enjoy juvenile court. The thing is, I don’t think it’s adversarial enough for me. It’s very much community-based, which I enjoy. I think it’s very beneficial at the end of the day for the child, where you have the prosecution and the defense (working together), very collaborative, very rarely do they disagree, and even the judge will agree with them, and we’ll have social workers and psychiatrists, psychologists that all come in and work to find the best response.

I like a more adversarial approach.

What do you like about it? Do you thrive on the challenge of verbal argumentation or what do you love about it?

I love the ability to stick it to the man, if you will. The idea of, again, the government is coming in and presenting whatever it is they’re presenting. I love nothing more than to cross examine witnesses from the government.

During the summer, I did some trials in juvenile court under a special license from the Illinois Supreme Court. I was able to work on cases and be on the record. So I was questioning Elgin police officers under oath and I loved it. Truly my thought is: we all make mistakes [in our] jobs.

But I love to be standing there and have the ability to poke holes in this beautifully drawn picture. Because very rarely is a case just black and white. Very rarely is there a recording of every incident that happened leading up to and after. So truly, I enjoy being able to come in and poke holes—because that’s what you do. The state presents you this beautiful picture of, We know it’s the guy because of this and that. But then you get to come in and say, Well, there’s no witness that says that he was there. The witnesses that are there don’t recognize him. You also have no footage. And you start creating doubt. So then the jury or judge can sit there and go, Yeah, if we’re gonna deprive this person, then we got to be sure. And yeah, and I enjoy that adversarial aspect of: You’re saying this? Well, I’m gonna say that. I don’t know. I just enjoy that.

In what ways do you see your training as a tutor apply in the work you do? Are there any ways that you see that training come to bear?

I mean, the Socratic method. It’s like all law school is. But when we’re sitting with writers, and they come in, instead of necessarily giving them an answer—because rarely do we have a set answer; rarely is it this is the way, it’s the only way—instead, we do a lot of questions. Like, why did you take this approach? Right? And then you get to hear the process, and the process might include, well, the syllabus says this or my professor says this or in my past class, so then you start getting a better understanding of where the writer is coming from to then be able to respond better instead of making all these assumptions.

And so I think that has been very beneficial when it comes to dealing with actual clients now, where they come in and you look at the report of the arrest, and you see that they were arrested for, I don’t know, anything, like reckless driving and endangerment of a third person. And so you can make a million assumptions by just reading that report, right? Because you’re going to read it and you’re probably going to take it for face value. Like, Yeah, that’s what happened. And then you’re gonna see their biographical data and start making assumptions about their background and how maybe that’s the reason that they did this. And you’re already assuming that they did something and you’re assuming why they did it. Incorrectly.

So the method that we implement here at the Writing Center, you come in with a fresh blank mind. Like you you don’t drop all the skills and knowledge that you have, but you really put that to the side for a second. You ask questions to better understand where the person is coming from, what they’ve experienced, how they see the situation, where they may have a strength, where they may be lacking something else, and then from there, respond to their needs.

I think that’s the most applicable out of all the things that I’ve learned here, where you’re truly like let me learn who you are as an individual, before passing judgment, before I start giving you advice on something that you’re living. Like, you are living this—this is your writing. This is your paper. These are your ideas. This is what you presented to me on a piece of paper. Let me learn about you before I start educating you or lecturing you on what you should and shouldn’t be doing, right? Because if I take that approach, I’m going to be wrong most of the time in thinking that I just know everything. Like, it doesn’t work like that.

And deferring to them as the expert on their intentions as a writer?

And here [with a law client], you’re deferring to their experience because they’re the ones that lived it. They’re the ones that were being charged with a specific crime, right? They’re the ones that have their family and have their background, they are the expert. You’re there with a training, but you’re there to apply that training to their experience, not the other way around.

Do you have a sense of what would be the ideal post-law school placement for you—what kind of place do you want to be at?

The public defender’s office. That’s as adversarial as it gets. Again, it’s a criminal law, it’s litigation, it’s adult court. That’s the ideal position. That’s what I want to do. And they always say that if you’re not in court on day one, it’s because you’ll be in court on day two. So you really hit the ground running. You go in there, you’re given files and you start with smaller cases, like you’ll start in traffic court where nobody’s gonna lose life or their liberty. But it truly is like you learn on the job. We get a lot of training at school, but then it’s obviously very different than when you’re in the real world. So it really is trial by fire. You’re learning as you go. You’re making mistakes. But they’re not super high stakes.. I mean, your client might be upset with you because you made a mistake, and now they’re applying a fine, and that’s no fun for people, but, then that trains you well to be taking on bigger cases if you want—your domestic violence cases, your felonies, your misdemeanors, all the things that are bigger, more stakes involved.

What’s the path to that? Do you do you get a clerkship?

No, I could start right out of school. The application process is actually soon. But yeah, you can start right off. So the process for that would be if I get hired, right out of law school, I would start as law clerk during [the interim]. And when I take the bar and pass, which usually [happens] by the fall of next year, I’ll get my certification and then they officially set you as an attorney. But during that [pre-bar exam] time, it’s like a provisional time of like, you’re hired, you’re working here, but you’re not an attorney yet. So they can’t give you the title yet or give you cases to take on your own but you assist other attorneys that are already there.

It’s not like you have to get a clerkship first.

I mean there are people that choose clerkships. I mean, clerkships are very highly sought and they’re very, very competitive. Those are especially like federal clerkships. And those are a lot of the people that end up being a federal judge or the Supreme Court. Those are very intense positions.

Is there any advice you’d give tutors about how to survive the post-grad transition? Some people know exactly what they want to do post-grad, but I think other people find that it’s not always easy to get your footing in a job or grad program right away. So I guess, what are your post graduation hacks or tips or advice you’d give people about how to survive that?

Obviously, there’s a limit but I think truly: take[e] opportunities that come up, even if it’s not your ideal position that you want right away. If you have another opportunity that doesn’t seem like the greatest—take it, because I don’t think any of us truly understand the value of networking, and the amount of opportunities that come from a few positions. So, for example, every position that I’ve applied, been offered and then taken has actually been a position that a mutual told me about. Even 222 {the tutor training class, now English 282]—one of my friends was like, Hey, I know you’re looking for a job, if you take this class then you can apply to be a writing tutor after. And I hadn’t heard about that before. And then from there every position I’ve had, I’ve been educated on other positions and then from there gone on, instead of just like loose Google searches, which for some people are very effective. And I have been offered some positions like that. But I’ve always taken the ones where I was referred to by someone.

Like I said, the immigration law [position] I really took not because I thought it was ideal, but because I thought: it’s flexible, I’ll make money during the school year. And then I realized that I enjoyed immigration law and that’s something that I might want to do a bit of in the future, and then it’s also connected me to all these attorneys. And then indirectly I’ve also learned a lot about criminal law that I wouldn’t have learned in my classes. In those classes we don’t talk about the intersection of immigration and criminal law. I’ve only learned that because of this position. I’ve been there for over a year now and I really enjoy it.

Smart advice. The word of mouth, personal, connecting thing—sometimes people can feel intimidated by that. But you can also make that work for you: talk to lots of people. Say yes to everything you’re invited to.

And then I also think another piece of advice is—and I know for some people it might not be as easy because we all have different comfort levels— but try to be a connector. Anytime anybody says anything remotely related to law school, I’m like, Take my number and I’ll connect you with other people because I realized that relationship that you offer, if I offer my support to 100 people,, then at some point, one of them— and it always happens— one of them will offer me support as well. It’s an exchange. And then I’ll learn about opportunities that I wouldn’t have before. If you connect other people, then naturally people will feel inclined to tell you about opportunities or to connect you to people that they know and then you branch out from there.

What is your favorite stress reliever these days? What’s bringing you joy?

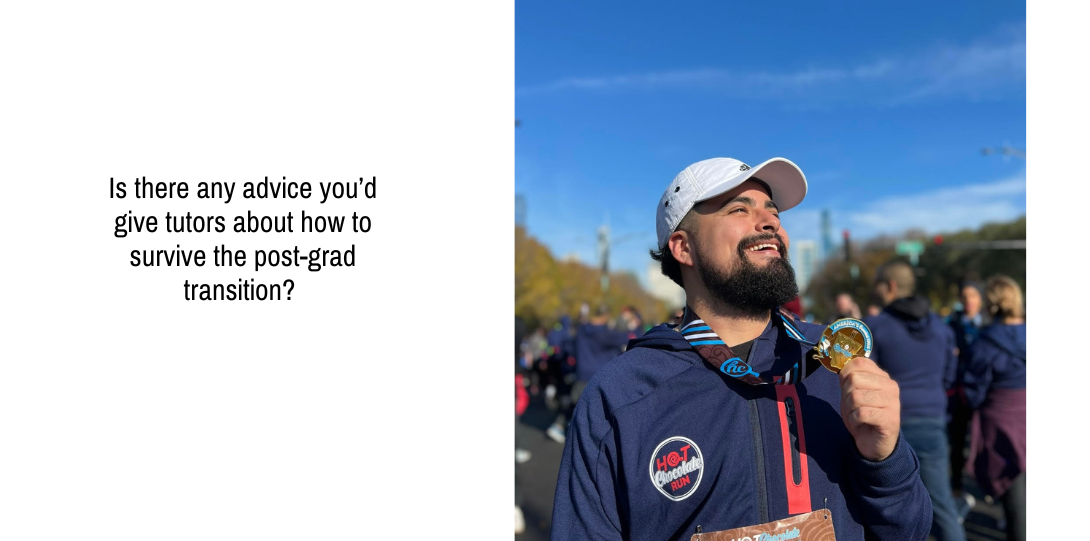

I recently ran the marathon.

Have you always loved running?

No.

How did you get into this?

I gained a bunch of weight during COVID. And then last year, the Chicago marathon had just happened. And I sat there and I thought, What if I run a marathon? And I was like, Okay, let me sign up for it. If I sign up for it, it’ll force me to train for it because I’m not going to sign up and not run it. And then I trained for it.

I didn’t tell anybody I was doing it because I was like, If I tell people and then I don’t do it. . . So I told my mom I was running the marathon three weeks before. I was like, Hey, don’t do anything on Sunday.

And then I told my brother the next day. My brother goes to IIT, he just started. And I was like, Hey, what are you doing two Sundays from now? He goes, I’m volunteering. And I was like, Oh, what do you volunteer for? He’s like, The Chicago Marathon. And I was like, Wait, really? He’s like, Yeah, my frat. We’re volunteering there. And I was like, Oh, cool. I’ll see you there. He’s like, You’re volunteering? I was like, No, I’m running. And he’s like, What—you’re running? Yeah. When did you start up? I was like, last year.

So yeah, that’s a nice stress relief, running.

Do you enjoy it now?

I enjoyed the training. I hated the actual marathon. It was torturous. It was just so— it’s 26 miles, right? So you don’t ever run 26 miles before the marathon.

How far do you go with training?

I trained for 18 weeks. I did an 18 week program. But the max that I ran before in one run was 18 miles. That means that I was missing eight miles. So mentally when I ran the actual thing at mile, like, 17—horrible. Also, you hit so many neighborhoods? So I was actually in Pilsen and Chinatown. That’s where the 17 mile hits. That’s where I was running. And I was like, I’m about to hit mile 17. And I was like, I hate my life. This is absolutely horrible.

And most people that train max out at 20. Point is, when I was running, when I finished, I have never felt so much relief in my life. And so much so that when I saw my mom a bit after—she was there—I started ugly crying. She was like Are you okay? And I was, Well, I’m in pain. But also, I’m so glad it’s done. I don’t regret doing it at all. I’m so happy I did it. One thing off my bucket list. But I don’t know if I ever want to do that again.

And then I said that and now I’m like, You know what? I kind of want to run the New York Marathon. I already did one. I know I can do it. Maybe I’ll do that too.

That must be really empowering for someone who’s never run to go from not being a runner, to being like, Actually I’m a marathoner.

And I mean, I played soccer in high school, but it’s very different. It’s very sporadic, you’re not just running in a straight line. So it’s a very different discipline, different willpower.

Are you just a hyper-disciplined person?

Not at all. I’m very, like, all over the place. I’m very go-with-the-flow. So this actually was super nice because it made me stick to a plan and a system and a routine for 18 weeks.

And you did it solo. You didn’t have a group or an accountability buddy?

I really didn’t want anybody. I really thought, I was like, Because then I’m gonna sit there and compete. Like instead of worrying about my breathing, my technique, if I do with people, I’m going to be worried about showing them that I’m not tired.

During the marathon, I had individuals that were old enough to be my great-grandparents that were passing me by in some instances. Yeah, but I had mentally already thought, I’m like: This is a race, yes. But I’m not competing with anybody. I’m competing with myself. I need to complete this because I set myself for it. And I just turned 26, so I was like, One mile for each year. So that was my whole thinking. And I was like, I need to do this. I don’t care if I’m the last person to finish. But I need to finish.

And I know that if I had done it with friends, there would have been that competitive part of it, and would have messed up my training, my technique, my mentality. If my friends are pulling up in front of me, then I’m trying to catch up. It’s a waste of energy. And I know that because I did the Chocolate Run, which was a 5k two weeks ago, with my friends. And that one we felt competitive about, and I was like, Oh, thank God I didn’t run the marathon with them. It would have been horrible.

Do you find it a stress relief now to run?

It was a stress relief while I was training, because it would be lighter runs plus I never did the whole thing. So even when I ran the 18 miles in training, I felt tired, but it felt good.

Was that a surprise?

I knew I didn’t hate running, but I’d never ever thought like, oh, let me do cross country or let me do long distance running.

There would be runs where I have music going and grooving with that, and then other times, no music.

And it was kind of therapeutic because then I would think about all these things that were stressful. But when you tire your body physically, when you exercise, it makes it harder to mentally stress about things. Because you truly don’t have the energy for it. So I would be like, You know what? I don’t have the energy to be stressed. It was one of those, right? Like we’ve all experienced that, anybody that’s ever exercised in any way. But this would be more constant because I would be running three to five times a week, for 18 weeks straight. So again, it was just this thought of like, I don’t have time to be stressed.

And you were in school at the time?

Part of it was during the summer but yeah, then the school year started and then I started adjusting my schedule, but always with the intention of, I need to do this many runs during the week to keep my program going. It made me a more structured person, so I found some benefit.

After that, after the marathon though, I didn’t run up until the Chocolate Run. And since the Chocolate Run. I haven’t run. So it truly is like I’m taking a break. But my intention is for winter break to restart again. Four weeks off, so it’ll be some nice chill time to pick it up again.