Salwa Sadiq, Writing Center Tutor Alumni Profile

12/5/23 Interview with UIC Writing Center Tutor ’21 alumna, Salwa Sadiq

12/5/23 Interview with UIC Writing Center Tutor ‘21 alumna, Salwa Sadiq (follow up to September conversation)

- Pronouns: She/her/hers

- Graduated: Spring 2021 with BA in Teaching of English

- Took 222: with Casey Corcoran sophomore year, F18

- Tutored: F18 until graduation in S21

- Currently: Lincoln Park High School Language Arts Teacher

We last spoke in September–now that it’s winter, do you have a big pile-up of papers towards the end that you have to get through?

Yes, it’s really challenging for me. I will put off grading until it literally can’t be procrastinated anymore and then have to take a sick day to get at least a portion of it done. I’m just now learning that that’s not an uncommon practice, even for seasoned teachers! I’m still trying to find ways to deal with that.

And how many students do you have? I imagine you have far more than a college instructor.

It’s around 130 kids this year.

Oh, that’s a lot.

Yes, thank you, by the way, for doing a second meeting.

What would be a good place to start?

The first time we talked, I think I presented as all-positive, and I want to be as accurate as possible for people coming into the field. The positivity I feel, now during year three of teaching, is genuine, but also something I have to seriously work to maintain and I don’t think it’s helpful to new teachers to only show the good parts. There’s a lot of stress and burnout I still can’t believe I survived to get here! But I’m really grateful.

You need a good support system in your school. It took me a couple years to find mine. I feel like the advice we always get as new teachers is “Just ask for help!” but that is totally not good enough advice. You need a whole mentor who generally shares your teaching philosophy. Idealistically, you need a whole network of people who understand your teaching philosophy and your efforts and who are willing to help you at the drop of a hat. It would be ideal for a school to have a program for new teachers, but I don’t think many do. CPS offers one called New Teacher Cohort Sessions, which is helpful.

I also feel like the “just ask for help” advice also kind of belittles the struggle that new teachers go through. A lot of times, you don’t even know what it is you need… you don’t know where to begin with your questions!

Resist the temptation to compare your year-one to someone else’s year-six and take it easy. Focus on building student relationships and on making your work and work for students as straightforward/simple as possible (level it up as you go). That’s advice I would give myself, based on how frazzled, idealistic, and perfectionistic I was in my first year.

All teachers struggle with planning, grading, communicating with parents, having healthy work boundaries… all of it. But more experienced teachers have found ways to cope, and so they won’t always present their own difficulties. So the best thing you can do for yourself is to prioritize health, relationships, and simplicity.

Advice from UIC professors that I still find useful: Forgive yourself everyday the same way you forgive your students. Just do what works for you. Focus on strengthening your strong points, and every other skill will follow. But year one, let go of all the noise of what a ‘perfect teacher’ is. That whole thing is a myth.

Use resources and practices offered by colleagues, but change it to suit you and your instincts. I spent a lot of time trying to ignore the issues I had with some curricula and practices. This year, that just wasn’t sustainable anymore. So after actually listening to those instincts, I’ve discovered some teaching philosophies and practices that go along with it. It means I might teach at a slower pace, and I might assign less homework, but my lessons can still be very effective. Now I know my priority is to make my lessons and my grading as simple and low-stress for me and my students as I possibly can. It took me a while to figure that out just because I spent a long time thinking I have to do what everyone around me is doing if I want to keep my job.

That’s really interesting. I wonder, do any examples come to mind of a point in the curriculum where you thought, “You know what? I wish I trusted my gut because I followed their curriculum, and I see it’s really problematic.”

Curriculum can be handed down to and across teachers. The very first one I was given felt problematic to me. The content was semi-adjacent to my identity and hit kinda close to home. We were using a book without teaching any context at all, which happens a lot for middle-eastern texts, and it ends in reinforcing harmful stereotypes. I didn’t know how to speak up about it to colleagues when I was still adapting to the hundreds of other stressors. I would just make my own resources and make mentions, but it felt like I was the only one concerned about it.

I definitely regret not speaking up earlier and more firmly, but again, my advice to someone else in the situation would be: don’t forget to take into consideration all the structures in place that keep you from feeling safe enough to speak up in the first place. That’s why mentorship is so important. It helps to have someone who hears you out and takes your perspective seriously.

And depending on the environment at your school, being culturally different, you might be a little too hard on yourself and not realize that there are structures that control large parts of your experience. Just like how you see student’s needs that go unmet, there are invisible things you might need that you aren’t always provided: extra time, cultural understanding, security, and consistent strong mentorship.

May I ask at your school, are you the only non-white teacher? And are you having to raise this point as a new idea for people, that teaching this book, without any kind of context, is actually just reinforcing stereotypes?

There are a small handful of non-white teachers in our department. I’m told it’s as diverse as it gets. It’s really nice to have people who get it and to be able to interact with friends after teaching all day.

And how do you feel? How does that feel for you having to be the advocate, in this role? And how do you feel people are doing in terms of listening and understanding your point of view?

On bad days, it’s isolating and frustrating. But I think every teacher should know (this is what I’d say to myself and to anyone in a marginalized group) that they are already doing so much on a day-to-day basis by being themselves and caring about their students. Constantly thinking on a grand-scale (even if it’s just a school- or a department-scale) can be heavy enough to weigh me down. At the end of the day, it gives me the most peace to know that at least all my students (that’s 130 people per year) know and have a good relationship with at least one Muslim person.

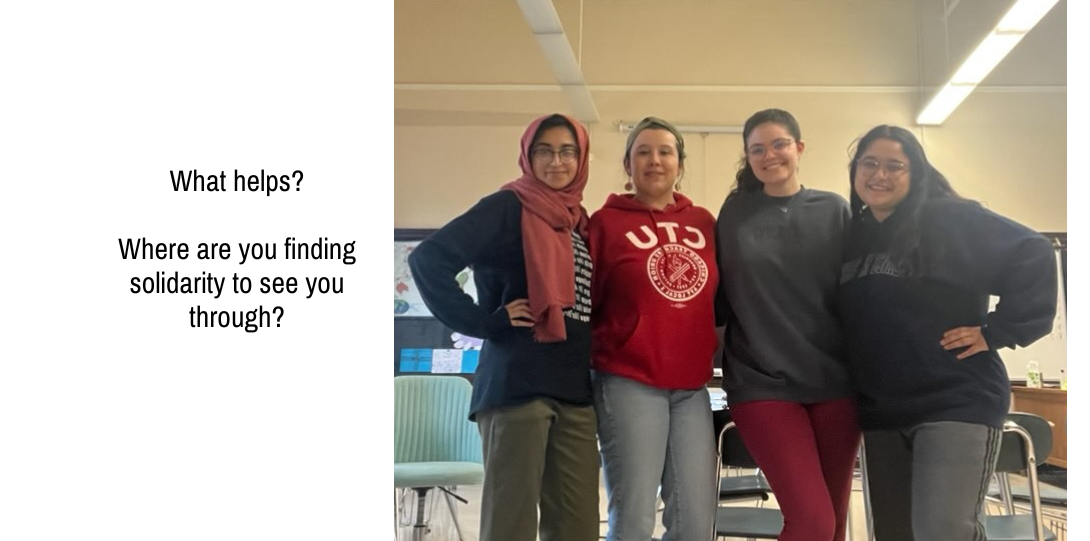

Do you feel like you have colleagues—maybe not on your team, but others—who can relate to what you are experiencing, this fearfulness around saying the wrong things, such that people just tiptoe around, without acknowledging things like historical or cultural context? Do you feel like you have colleagues who get it? Who are like, yeah, I’m experiencing that, too?

I have a few that are also non-white teachers in the department with similar experiences. We don’t teach on the same team, but having a little crew of understanding and caring teachers of color is unbelievably helpful. They also have experience with similar issues. The past few months have dialed up all the cultural discomfort I’d been feeling in such a culturally un-diverse space. On a personal level, I have had to kind of tell myself to stop chasing after and seeking the understanding of (mostly white) teachers.

It really helps to be in a bubble, every once in a while, of teachers who worry about oppression very frequently because we not only see it in the world, but we can also feel it in our classrooms every single day.

My colleague who has kind of taken the mentor-role for me said that sometimes, it helps to go find your bubble, and you might not find it here [at work], but find it. Yes, we can focus on holding people in power accountable, but for many reasons, it’s also wise to remember that there are many people who already get it… who you don’t have to educate or convince or appease. Go find them and seek to understand them.

What would happen if you said, I want to teach about the history of Palestinian oppression. I want to talk about what’s happening in the moment? Do you think the school is censoring teachers? Have they said explicitly that we can’t educate about this? Or are you just inferring from the silence that they’re uncomfortable doing it?

There is definitely tension, and teachers do need to worry about protecting themselves. No one has ever said we can’t teach it. I think we were encouraged to discuss it at some point but were not given any guidance or protection around it, or even an intent to do any professional development or our own learning before teaching it.

There was discussion about removing a poem by a Palestinian poet from the curriculum for this year. It’s been the first time I really stood up about anything. There was a ton of discomfort around it. Arguments against reading it were coming from a place of worry and care for emotions in the classroom but also just out of fear and lack of knowledge. There were concerns about it making the classroom a less safe space and about parent- and student-pushback. But of course that kind of fear comes from a lack of knowledge. Our taxes have funded the killing of over thirty thousand people only since October, and still so many of us are still so apathetic about it. Ignoring it isn’t doing less harm.

Wow. yeah.

A safe space for who, I mean?

Do you see a way forward with any of your colleagues saying, actually we’re doing a disservice to our students in terms of education. to not give them facts about the history and what is happening? It’s our moral obligation as ethical agents to teach the truth?

Yes, and they were receptive to discussing it. I was trying different arguments, like, if we were alive during the Holocaust, and there happens to be a poem about it in our curriculum, are we going to remove it because it’s too relevant? That doesn’t make sense. And, if we know that we have Jewish students, and we know that we have a few Muslim students, and we know that we have Palestinian students, — then we know that they’re probably being affected. Then [“keeping kids safe”] is not a reason to ignore it. [In the name] of creating a “safe space in a classroom,” we’re actually making our school a less safe place for everybody. It doesn’t make sense. There was even discussion about an alternative poem for some students. And to give some perspective to that, I said, when we teach poems on Black struggle in America, are we gonna offer white students a different poem to avoid it? It’s its own kind of racism, deciding which students will have which experiences.

I do see that it’s kind of turned around, like I know at least a couple of other teachers taught it. It was honestly so stressful for me that I was kind of falling apart and not functioning well for a few weeks… which makes sense thinking back. All the “advice” I’m giving right now (about finding mentors, trusting your own gut, stop seeking validation) are the things I really didn’t learn myself until this experience.

But it was such an important lesson because it helps me lean into my other instincts that I was too scared to follow.

For example, sometimes I just keep hearing about how incompetent or uninformed or careless kids are. But that’s not the whole reality. Are kids uninformed or they just need to be informed? Are kids apathetic or just overburdened without any guidance? (I know that as a teacher, my needs aren’t really met, and I have to know how that affects my students. I know that my lack of information becomes theirs. My apathy becomes theirs. My stress becomes theirs. That’s why it’s important to have a trusted mentor to help you manage your own wellbeing in such a wild system.)

There are a lot of classic systems in place that might be stunting learning today. Normally, we assign homework, then we ask them, Okay, what doesn’t make sense to you? But they didn’t do the homework. [so they don’t have questions.] Or, they’re pretending [they did the homework], and they’re too scared to [blow their own cover.] So they’re just like, Yep, I got it. [No questions.] So there’s a whole culture or a whole system that we have that stops kids from asking questions, which is such a lifelong learning skill.

And I know this whole homework scam culture from a student’s perspective because I was there just yesterday! So if you’re a younger teacher, you can maybe empathize more easily with the situation students find themselves in. That’s such a huge advantage. If there is something children don’t know that we feel they should know, we can teach them. Find the avenue that is interesting for them, let them ask tons of questions, and go from there! That’s my strategy for teaching now. I don’t rush the pacing. They are receptive to the content. I’ve prioritized classwork over homework, quality over quantity, so I’m listening to my teacher instinct, which means listening to kids and myself and being flexible.

So I don’t know. Things are changing. So new teachers should really stay in tune with their own instincts because it will probably make them better teachers, no matter how long that takes. I’m still a newer teacher, but when I think about even newer teachers my heart just goes out, and I feel as compelled to help them as I do students because they are just as important and deserve all the help and more.